I was reminded recently of some exceptionally hard men and their ability to adapt to remarkably difficult conditions, which brought up questions about will and suffering and how one develops mental toughness, which is often the decisive factor in sport performance.

Louison Bobet won the Tour de France three times in a row but 1955 is often heralded as his most astonishing victory, sitting solidly as it was, on a foundation of sheer stoicism and will power. He won stage 11 on the Mont Ventoux to move into second place after Ferdi Kubler made an early and optimistic attack, setting a "torrid pace" that eventually faltered, causing him to abandon the race. Bobet won after teammate Jean Malléjac collapsed (he was unconscious for 11 minutes before being revived). Interestingly, it was on that stage Bobet feared his saddle sore had reopened. He gritted his teeth and hid the condition from his competitors but no one could help noticing that during the final time trial he was in too much pain to sit down and covered the entire 43 mile-long stage standing up! Following the 1955 season he underwent surgery to fix the saddle sores that resulted in a reported 150 stitches, making his TdF win all the more remarkable. In the Psychological Training chapter of my book, "Extreme Alpinism", I ask, where does this strong will and hardness come from? Hardness is earned by recognizing desires and goals and enduring what ever it takes to fulfill them. To do this, the goal must be important enough to sustain you through the hard efforts and persistent training. A strong will comes from suffering successfully and being rewarded for it. I always pose the question: does a strong will come from years of multi-hour training runs or do those runs result from a dominating will? There is no right answer because all actions are connected to, directed by, and a result of one’s will.

In 1981 Leonid Matveyev wrote, "Strong will is developed by overcoming difficulties. The difficulties have to be overcome systematically, not occasionally, and the increased degree of difficulty should not make them impossible to overcome. An athlete must be taught to carry out the training or competitive task. It must become a habit to always finish an assignment and to be dependable. An athlete must be convinced that there are no easy shortcuts to sports success, and as this success comes closer the degree of effort increases."

Thomas Kurz warns against allowing athletes to quit a training or competitive task because it, "lets the athlete learn a lack of commitment (and) that results in a habit of ceasing to struggle as soon as the level of difficulty increases." We form habits so quickly that very few instances of quitting without consequence are needed to form psychological barriers against digging in to continue despite pain in the future.

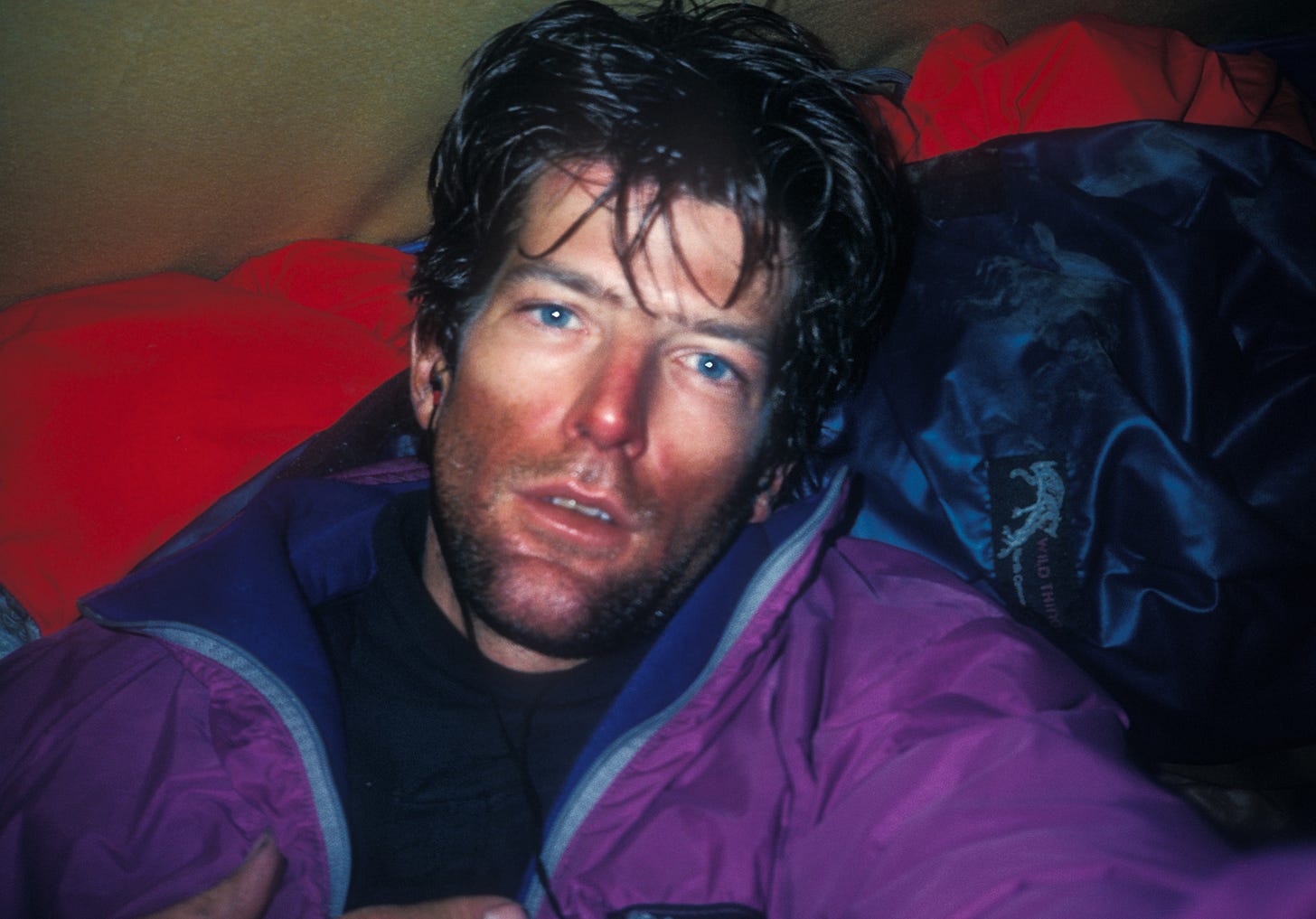

Mountain climbing was a tremendous teacher in this regard because I was often forced to overcome (what amounted to) trivial but effective mental barriers by difficult conditions or a developing situation on a climb. High-risk situations forced me to break bad habits in order to survive. If caught by storm on a hard, dangerous climb in the high mountains most climbers make a superhuman effort to live and often surpass their own acknowledged limitations in the process. By doing so they live into a new self-image produced by that higher performance and this allows them to develop new expectations of themselves, and new habits. Actively seeking situations where the consequences of failure spur greater effort and make you shuck the chains of self-limitation is a powerful tool of growth for those who are willing.

One of the finest examples of such overcoming occurred in 1961 when Walter Bonatti, Pierre Mazeaud and five other climbers were trying to make the first ascent of the Freney Pillar on the south face of Mont Blanc. Caught by a savage and exceptional storm within striking distance of the summit the team elected to sit it out, hoping for the weather to improve. When it didn't they were forced to descend but had expended such vast personal resources that four of them perished in the process. Later Mazeaud was asked why the youngest had died, and he replied,"The eldest are more resilient (Ce sont les plus vieux qui résistent le mieux!)". They died in the order of age, and arguably, experience. The older climbers had greater experience and more firmly entrenched habits, and more psychological resilience to rely upon.

Bonatti was known to undertake winter climbing practice in the Grigna (near Lecco, Italy) where he would self-impose a cold Saturday night bivouac then climb a route the following day regardless of the conditions. He constantly put himself in situations that tested and formed his remarkable abilities, making up-against-it performance a habit. Austrian climber Herman Buhl carried snowballs in his hands to develop both psychological and physical tolerance to the cold, and he climbed on his local crags all winter long, even in stormy conditions.

We tried to replicate similar learning situations and outcomes in my old gym despite the inherent safety of the controlled space; we used social risk to threaten self-image because (we imagined) it could be just as influential as the prospect of the long fall. And while this can produce positive habits in relation to quitting an artificial albeit difficult task, the deeper philosophical lessons related to actual risk, consequences, personal honesty, self-belief in dire circumstances, and discriminating real and false value, may not be learned in such safe conditions. And yet, the anxiety-inducing challenges we created helped those whose training experiences had been too comfortable to develop resilience they couldn't learn in less pressurized situations.

The mind and body are frighteningly adaptable; to both comfort and its opposite. A progressive cycle of stimulus and response can help the mind adapt to just about anything. Norris McWhirter, Roger Bannister's timekeeper for most of 1953, once described how Bannister's efforts on the inclined treadmill in the Oxford physiology lab prepared him mentally to break the four-minute mile barrier saying these sessions were so hard that, "anyone would break. You poured sweat, your spine turned to rubber, and driving up the incline there was the most extraordinary effect on your chin and knees meeting in front of you … Roger himself ran to breaking point on at least 11 different occasions. Compared to that, the four-minute mile was like a day off." Effectively, Bannister prepared himself mentally so that, on the day, the level of effort required to run sub-4 was not psychologically insurmountable. He had already run 10x 400m in 59 seconds each with two minutes rest between intervals so it was not an illogical step to string four of them together.

A cycling acquaintance described to me how it often felt to do the 1000m TT on the track, "In efforts lasting 1:05 to 1:07 I definitely had the opportunity to see God when the legs started to load after 700 meters and I struggled to maintain my speed through the blinding pain: tunnel-vision and temporary deafness in the final 300 meters were good indications I was performing well." This is clearly a terrible experience but one he readily volunteered for — repeatedly — and retrospectively he admitted that, "this psychological conditioning to self-inflicted physical pain served me in later years during periods in road races when I was on the ragged edge and didn't have much left to give."

It's all training, or it can be if A), you are preparing for something and can tie the effort and pain to achieving that objective, and B), you have the wherewithal to learn the lessons such effort is broadcasting every time you dig deep enough to access that frequency. Circle back to Matveyev's declaration that you must confront these difficulties "systematically, not occasionally" and you will understand why I imposed difficult physical and mental challenges on my trainees with such alarming frequency.

Unfortunately, we are convinced by media and sales pitches, the talk of the ignorant and the bio-hackers that we can have access to the physical and mental tools necessary to succeed (and evolve) with relatively little investment and even less time. The truth is different and far less marketable. Besides, those who are willing to do the hard, disciplined work have already done it so they aren't susceptible to the promise of a "four-hour miracle" or "cure in a bottle". Figuring out how to do what's hard and then putting that into practice can take years. Mark Allen lost six Ironmans before winning in 1989. He credits that win and the next four to finally having accepted that, to win, he would have to give what the race demanded and not stop ever-so-slightly short, giving only what he was prepared to give, which was good enough for two 2nd places, a 3rd, two 5th places and a DNF in his first six tries.

Still more demonstrative of the mental toughness he developed over many years of practice is his internal negotiation during the run leg of the 1995 Ironman. Allen came off the bike 13 minutes behind the leader and over the course of the next 26 miles fought the subversive self-talk within that urged him to slow or stop. Instead, he hunted Thomas Hellriegel. Allen had already won in Kona five times, he could easily have slowed up or dropped out altogether without affecting his position in the sport. That he continued, fighting from so far behind, and won is one of the greatest triumphs of on-the-fly sport psychology I have ever heard about. Truly, the man knew how to suffer.

The time and energy it took for Allen to learn the lessons and do the training that allowed him to so thoroughly dominate Kona in that era isn't available to most of us but we can learn from him and apply the concepts in accordance with the time we do have.

At various points I have written that, "some athletes know how to Hurt while others know how to Suffer." In the gym context I used the term Hurt to describe the outcome of a savagely hard but relatively short effort. Some athletes want to succeed badly enough that they readily accept the consequences of a cardiovascular Divine Wind, of balls-to-the-wall self-immolation. Repeatedly undertaking efforts of this intensity and duration—no matter the emotional cost in the moment—can change habits and attitude but don't offer the opportunity to witness alterations to one's internal landscape in real time the way longer efforts do. In this context I used the term Suffer to describe what happens during and after a less intense but far longer lasting effort. Duration has its own special quality, a shovel to dig deeper and deeper as time and effort accumulate; meaningful self-confrontation doesn't occur in the early minutes of an event. We need time to examine ourselves, to contemplate settling for second or a DNF, to wonder if we will make it back to safety, to negotiate, and to affect the outcome of such internal discussion.

In the gym, there wasn't time for challenges of such duration so the training sessions often tested a trainee's ability to Hurt whether s/he had the temperament for it or not, or whether the adaptations produced were relevant to the athlete's actual goals. Many of them grew and changed enough that we were comfortable calling the work successful. Some trainees, however, had their eyes and minds opened to the power of other, more difficult and lasting crucibles so although the deep psycho-physical changes we sought to induce weren't available indoors, what transpired there produced the mental toughness to undertake truly transformative efforts outside of the gym.

I have always held that hard physical effort affects deep psychological growth, with the caveat that the effort must last long enough for one to observe and potentially, steer the outcome. It can happen all at once if the experience pushes one to and beyond the edge of the possible but generally, the accumulation of lesser experiences pour the foundation of meaningful, enduring change. Pushing the boat past the horizon cannot happen as frequently as we may "systematically, not occasionally" challenge our capacities on a smaller scale so we must use what resources are available. Conscious movement done with enough intensity to trigger anxiety or fear changes our view of what is and may be possible. Overlaid on personal environment, this edits the map of opportunity, growing our appetite for ever more powerful experiences, and a gateway to higher Self.